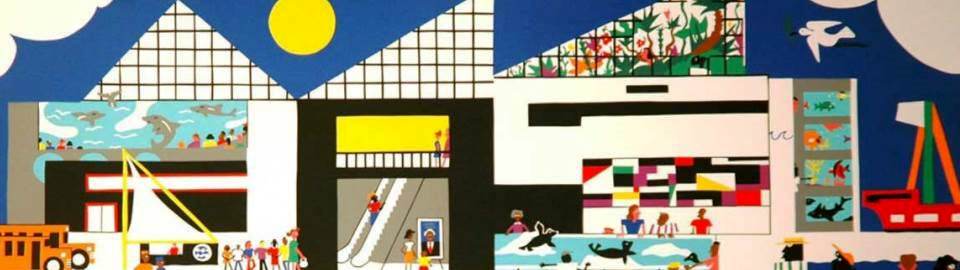

National Aquarium in Baltimore, 1994, Edition no: 32/75, Screenprint, (image: courtesy Steven Scott Gallery)

The In and Outsiders

view the exhibition | watch artists’ talk

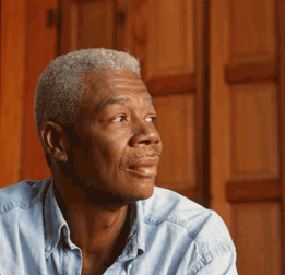

During his high school years, Tom attended Carver Vocational High School (1963) and went on to earned a scholarship to the Maryland Institute College of Art where he received both his Bachelor of Fine Arts (1967) and Master of Fine Arts (1987) degrees, subsequently retiring from teaching after 20 years in the Baltimore City School system to become a full-time artist. He was influenced by black artists such as Jacob Lawrence and Aaron Douglas, evidenced in his use of flat color shapes, and the writings of Langston Hughes. He also drew inspiration from patterns analogous to those found in traditional American quilt-making.

Miller was commissioned by the Mayor’s Advisory Committee on Arts and Culture to create six murals from 1991-1998. Of them five remain, and are a testament to his creative genius. They continue to bring beauty in the midst of blithe. The murals grace the walls of buildings in Baltimore’s inner city and are themed around racial pride and the concerns of the black community. The artist used brightly colored and at times whimsical figures to conveying messages of hope and self-determination.

In one of his most powerful murals, Miller depicts a black silhouetted man with a muscular physique wearing a white T-shirt. The black figure, surrounded by an exotic setting, is seated on a yellow sand beach holding a book. Above him is a bright blue sky with a white puffy cloud. There is a tall flower which towers over him and he is joined by a curious bird who sits perched by his side. On the pages is an African proverb: “However far the streams flows it never forgets its source.” Here the artist sought to inspire young men, and of this mural he commented “I wanted to say a person could travel and expand his mind through reading.” And there’s the more subtle message “that you can’t be a strong African American male — or any male for that matter — without being literate.”

Miller gained a reputation as being one of the most renowned contemporary artists of Baltimore. He distinguished himself though his self-described style of “Afro-Deco” painted furniture pieces. Tom recycled old objects, tables, chairs, cabinets and bookcases in his art furniture making. He used color and pattern, statement, satire, and whimsy in an African American vernacular where he cleverly fought against racial stereotyping; and in doing so, created an iconographic system of his own. Miller’s objects, both utilitarian and works of art possess iconic images of animal motifs, Aunt Jemimas, pink flamingos, fruits, birds, palm trees, and watermelons juxtaposed with black faces to address social injustices using humor and wit.

In contextualizing Miller’s painted furniture in a 1991 essay, Lowery Sims, then curator of the Metropolitan Museum of Art draws parallels between the artist’s work and Dahomey textiles, 18th century French furniture makers and 19th century African Americans “who successfully created a synthesis of African decoration and European cabinetry”. Sims suggests these elements are evidenced in Miller’s art furniture making. Lowery Sims, Ph.D. is currently curator for the Museum of Arts and Design in New York.

Traditions unique to Baltimore’s African American community were the themes of Miller’s 1994 screen prints. In “Summer in Baltimore” located at 1339 E. North Avenue, he depicts a black arabber with horse-drawn cart selling watermelon. In the shadow sits the Washington Monument and a patron who peers hungrily from a window awaiting a bite of the delicious fruit. In its companion screen print “Maryland Crab Fest”, Miller draws from his African roots as he portrays a family gathering. Seated around a table covered with crabs is a young man wearing a kufi cap, he is joined by another donning a Malcolm X T-shirt, and a girl with “big Baltimore hair” inspired by traditional African braiding. Other family members and animals join the feast as music blares from a boom box.

In 1996, the National Aquarium in Baltimore commissioned Miller to create what would be his final screen print titled “The National Aquarium in Baltimore. In it, the artist depicts school groups and families of all ethnicities visiting the national treasure. The imagery is filled with joy, conveying the artist’s affinity for the aquarium which was one of his favorite places in the city.

Miller became one of the first African American artists from Baltimore to be granted a one-man show at the Baltimore Museum of Art in 1995. His work has also been featured in group exhibitions at the Smithsonian Renwick Gallery, Washington, DC; American Craft Museum, New York; Studio Museum in Harlem, New York; and Contemporary Art Centers in New Orleans, Louisiana and Cincinnati, Ohio.

His works are in the permanent collections of the Academy Art Museum, Easton, Maryland; and Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore; Maryland Historical Society; Reginald F. Lewis Museum of Baltimore, Maryland; and the University of Maryland University College in College Park, Maryland.

On June 23, 2000, Miller died at the age of 54 after an 11 year battle with AIDS at The Joseph Richey Hospice in Baltimore. He will always be remembered for his beautiful art, wit and charming personality.

References:

Adams, Eric. “Neo-Romanticism on Display at Steven Scott.” The Sun. Baltimore, MD. 24 May 1991.

Dorsey, John. “Veneer of Humor Covers Furniture of Tom Miller.” The Sun. Baltimore, MD. 12 May 1993.

Dorsey, John. “A Showcase of Black Art.” The Sun. Baltimore, MD. 23 January 1990.

Sims, Lowery. “Tom Miller’s Afro-Deco.” Exhibition Essay, Steven Scott Gallery, Baltimore, MD. Nov. 1991.

Murphy, Eilleen. “Tom Miller Obituary.” City Paper. Baltimore, MD. 28 Jun 2000.

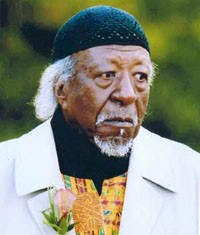

Andy Pigatt (1928-2009) was born in Raeford, North Carolina, October 20, 1928. He received vocational training in general woodworking and carpentry at George Washington Carver High School. Pigatt served in the United States Army in 1950-55; studied cabinetmaking on the G.I. Bill after leaving the military; and apprenticed under James W. Leach, Baltimore, Maryland in refinishing and repairing period antique furniture.

Andy Pigatt (1928-2009) was born in Raeford, North Carolina, October 20, 1928. He received vocational training in general woodworking and carpentry at George Washington Carver High School. Pigatt served in the United States Army in 1950-55; studied cabinetmaking on the G.I. Bill after leaving the military; and apprenticed under James W. Leach, Baltimore, Maryland in refinishing and repairing period antique furniture.

Pigatt performed free-lance work in New York after 1963, working for firms such as Worldwide Antiques, Leonard’s Antique Gallery, Knapp and Seigal Antiques, et al. Restoration experience includes work on Chippendale, Jacobean, Sheraton, Queen Anne and other types of collections.

Anderson launched his sculpture career late in 1960’s. A self-taught sculptor, his work is represented in a number of private and institutional collections.

“Nigger Chained” a seminal work is in the permanent collection of the Schomberg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York. Other sculptures are in the Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, New York; Reginald F. Lewis Museum, Baltimore, MD; and the American Visionary Art Museum, Baltimore, MD.

Pigatt participated in exhibitions sponsored by the American Federation of Fine Arts, the Urban Center of Columbia University, the Harlem Council and Bell Telephone Company. From December, 1967-1976, his work was exhibited in such venues as the Empire State Building, Observation Tower, New York, NY; The Pam Am Building, New York, NY; the Brooklyn Museum, New York, NY; Columbia University, New York, NY; Elma Lewis School of Fine Art, Dorchester, MA; University of Florida, Gainesville, FL; Milliken University, Decatur, IL; Reading Public Museum and Art Gallery, Reading, PA; University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI; and the Illinois State Museum, Springfield, IL.

Significant exhibitions include: “Black New Artists of the 20th Century: Selections from the Schomburg Center Collections”, 1970; traveling exhibitions “New Black Artists”, 1971 and “Black Art – Ancestral Legacy: The African Impulse in African-American Art”, 1989-91.

Anderson’s work was favorable reviewed and commented upon by such notables as John Canady of The New York Times on October 8, 1969, with a headline stating “Sculpture Is Strength of ‘New Black Artists’ Show” and Robert Taylor of the Boston Globe on November 22, 1973 with the headline “Anderson Pigatt’s sculpture seen in ‘Speaking Spirits’”. Other comments and accolades come from correspondence from Thomas W. Leavitt, Director of the Herbert f. Johnson Museum of Art at Cornell University, Joseph V. Noble, Vice Director for Administration at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, and Dr. Robert Bishop, Director of Museum of American Folk Art in New York.

Mr. Pigatt was selected to participate in the exhibition and publication, Black Art Ancestral Legacy, sponsored by the Dallas Museum of Art, which showed at the High Museum in Atlanta, the Milwaukee Art Museum, and the Virginia Museum of Fine Art in Richmond. His work has been purchased by such notables as Singer Richie Havens, artists Andy Warhol and John Biggers.

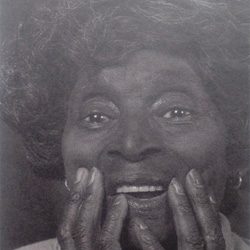

Elizabeth T. Scott (1916-2011)grew up in Chester, South Carolina, the sixth of fourteen children. There were seven brothers and seven sisters. Her father sharecropped the land where her grandparents had lived as slaves. “He was a sharecropper and we were sharecroopper’s children. Victims,” she says. The tradition of quilting was an integral part of the rural black American experience. Elizabeth’s mother and father quilted. At the age of nine, she began her first quilt and has since developed into an extraordinary artist. Her images not only ellicit rememberances of Africans’ past but evoke new visual traditions in the display of bright colors, complex pattern, animals, buttons, rocks, and “monsters” that grace the stitched surface of her quilts.

Elizabeth T. Scott (1916-2011)grew up in Chester, South Carolina, the sixth of fourteen children. There were seven brothers and seven sisters. Her father sharecropped the land where her grandparents had lived as slaves. “He was a sharecropper and we were sharecroopper’s children. Victims,” she says. The tradition of quilting was an integral part of the rural black American experience. Elizabeth’s mother and father quilted. At the age of nine, she began her first quilt and has since developed into an extraordinary artist. Her images not only ellicit rememberances of Africans’ past but evoke new visual traditions in the display of bright colors, complex pattern, animals, buttons, rocks, and “monsters” that grace the stitched surface of her quilts.

Elizabeth T. Scott provides the annals of history with a critical challenge to address the aesthetic contributions of blacks in the New World. More importantly, she presents us with the aesthetic continuity of deep-seated traditions, practiced over generations of time through the linkage of the extended family. We have few records of the African-American families who had active and continuous histories of involvement in the plastic arts; the creative energies of Scott and her family have prevailed where others have yet to be discovered.

Scott practiced her art until 1940, when she moved to Baltimore and ceased to make quilts on a regular basis. Through the constant encouragement of her daughter and her friends, Scott began to quilt again in the mid-1970s. She developed a remarkable body of work and began to exhibit her quilts in conjunction with the work of her daughter, Joyce Jane Scott, a mixed media-performance artist, at Gallery 409 in Baltimore and the Art Gallery of the University of Maryland at College Park. Scott worked relentlessly, and as she produced more quilts, she was invited to teach and lecture at colleges, universities, recreation centers, special workshops, and senior citizens’ groups throughout the state of Maryland. She was asked to exhibit and lecture at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Studio Museum in Harlem, the Smithsonian Instutition’s Folk Life, Festival, as well as at numerous galleries along the east coast from New York City to Washington, DC.

Scott worked intermittently on that first quilt, begun at the age of nine, for fifty years–hence its title, the Fifty Year Quilt. Her mother, Mamie, took an active interest in Scott’s selection of cloths and colors; at one point, Scott recalls, her mother made her remove a square from the lower right corner because it was too bright. The Fifty Year Quilt is embellished with embroidery and stitchery that form images and symbols of flowers, stars, and animals.

The Plantation Quilt, one of a new series completed in 1979, is conceived from a double perspective. The stars, which are placed almost randomly across the surface, approximate their positions in the sky on a clear evening, just as they might have been seen by women who sat out on their porches sewing and piecing after a long, hard day of work. The stitches under the star pattern take on the contours of a farm, with rows of stitching standing in for the rows of crops. “That’s the way the fields were surveyed off,” Scott explains. “Every corner had to be filled. There were no leavings, no spots in the field. The fields had to be finished.”

-excerpted from the WCA Honor Awards Program of the National Women’s Caucus for Art Conference, Boston, MA, February 10-13, 1987