Curatorial Statement

Curatorial Statement

Blackness and the possibilities of its future are the impulses that drive the imaginations of African American artists who draw inspiration from Afrofuturism, Black existentialism, spirituality, and futurist thought to construct a Black universe of tomorrow. Imagery rooted in nuances of the Black experience offers counter-narratives that confront fictionalized characterizations of African Americans and cultural Otherness and offers, in place of them, the essence of Black humanity.

In The Afro-Futurist Manifesto: Blackness Reimagined, artists assert agency over narratives of Black life, offer discourse into the socio-political concerns of African Americans, and pay tribute to the resiliency, creativity, and spirituality that have historically sustained Black people.

The concepts of time, space, and existence serve as the framework for exploring Blackness and its speculative future. Time, for Arvie Smith, serves as the metaphor for allegories that reinterpret Greek mythology, presenting Black women as goddesses. Preach It and Cupid and Psyche are testaments to the strength of Black women and battles fought for autonomy over their bodies against iniquitous systems of oppression. M. Scott Johnson turns to African American folklore, Afrofuturism, and Afro-surrealism in The Metamorphosis of High John the Conqueror: Tribute to an Afrofuturist Deity to make tangible the spirit of High John the Conqueror, the time-traveling shapeshifting folk hero manifest in the psyche of the enslaved. Felandus Thames’s Space is the Place and Door of the Cosmos, synthesized in the tradition of Black improvisational music and the futurist philosophy of Sun Ra, explores the spirituality of “Black Interiority divorced of references to the corporal body and its relations to trauma, objectivity, and labor.”

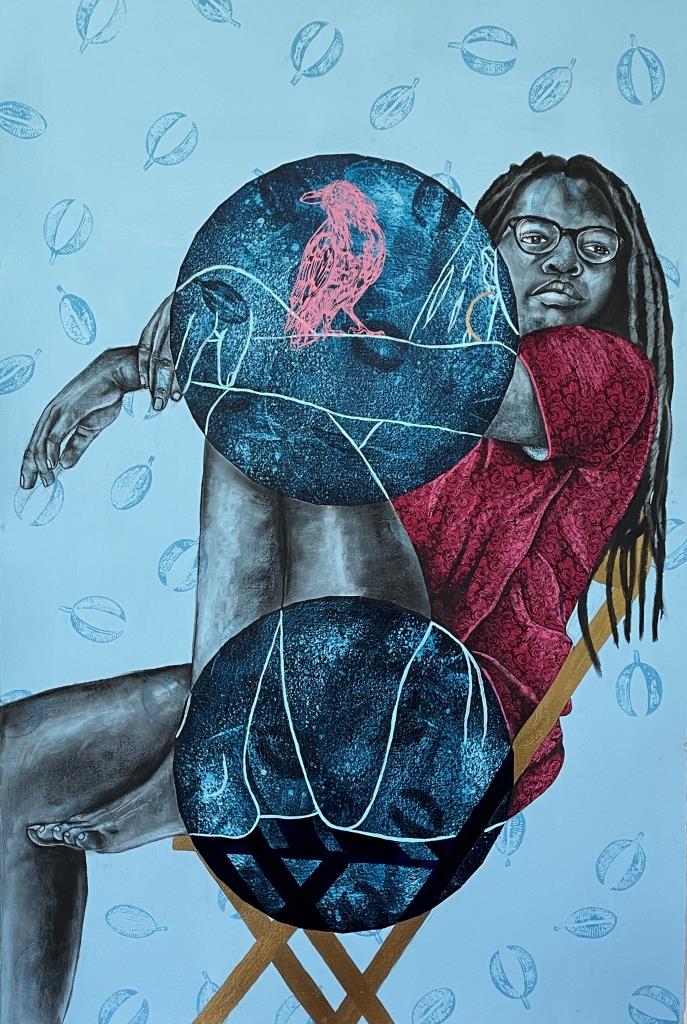

Space leads to Larry Cook’s series The Other Side of Landscape, vernacular photographs that challenge the structure of the U.S. prison industrial complex and its 40 percent Black population. Through digital manipulation, prisoners who once occupied the “yard” are liberated. The barren landscape becomes the “escapist backdrop for a system free of human captivity.” Morel Doucet’s assemblage portraits address environmental racism. In After All That, We Still Stand (When Black Lives Look Blue), colorful silhouettes surrounded by flora and fauna provoke commentary on the displacement of Black people from their homes and communities. Delita Martin’s prints Visionary and Follow Me Little Bird explores Black women’s spirituality and ascent to a higher self. The overlapping of portraits, patterns, colors, and textures form liminal landscapes, “veilspaces,” as portals where the spiritual and waking worlds coexist.

Existence, as portrayed in photographs by Tawny Chatmon, centers Black children in Italian landscapes as a reaction against the historical erasure of Blackness. In Chatmon’s Pastoral Scenes series, Monique in Pastiglia and Ahmad in Pastiglia are influenced by the work of 15th-century Italian artists (such as Vittore Crivelli & Fra Angelico) and the practice of Pastiglia. They are adorned with African symbolism, which celebrates their ancestry and affirms their preciousness and humanity. Interpreting the inherent possibilities of Black youth free of negative stereotypes is the impulse that drives painter Monica Ikegwu. Subjects rendered through the lens of a Black aesthetic represent the next generation of leaders: Chidera, Brandee, and youth featured in We Outside exude confidence as futurists who will fight for societal change.

Myrtis Bedolla, Curator

artwork:

Visionary, 2021

Relief Printing, Charcoal, Pastels, Acrylic 40×60 (unframed) 2021

60 x 40 ″

Delita Martin