Delilah Pierce-Biography

Delilah W. Pierce (1904-1992)

Biography

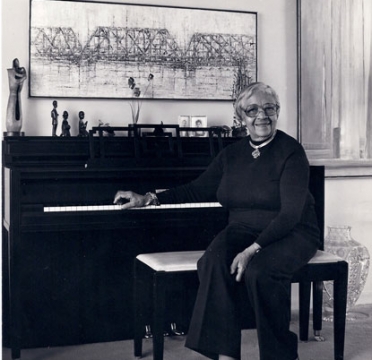

Born in Washington, D.C., in 1904, Delilah W. Pierce served as an educator, artist and curator. Her artistic abilities were discovered at an early age by a teacher who found it difficult to believe that she was able to draw so well.

Born in Washington, D.C., in 1904, Delilah W. Pierce served as an educator, artist and curator. Her artistic abilities were discovered at an early age by a teacher who found it difficult to believe that she was able to draw so well.

Delilah is known for her fluid style, which ranged from figurative to abstraction. Her colorful compositions are inspired by nature, social justice, and her travels to Europe and Africa. Pierce was revered by her peers and according to art critic Judith Means, “The way she perceives the world, with joy and optimism, and the stunning clarity of her finely-developed aesthetic sense are integral not only to her character but also to the vivid visual textures of her work.”

view exhibition | watch panel discussion

Delilah had numerous solo exhibitions and exhibited in more than 150 group shows. During the course of her professional career, she participated in exhibitions with preeminent African-American artists: Elizabeth Catlett, Margaret Burroughs, Richard Dempsey, David Driskell, William H. Johnson, Lois Mailou Jones, Jacob Lawrence, Hughie Lee Smith, Alma Thomas, James Wells, and Charles White.

Her works were featured at: Barnett/Aden Gallery, Cosmos Club, Corcoran Gallery, Howard University Gallery, Margaret Dickey Gallery, Smithsonian Anacostia Museum, and Smithsonian Institute in Washington, D.C.; Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, Maryland and Hampton Institute (University), Hampton, Virginia and Kenkeleba Gallery in New York.

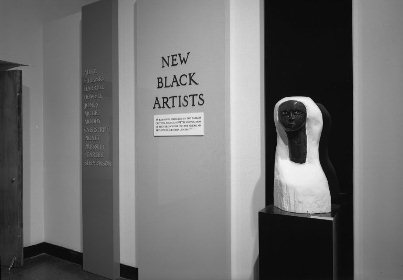

In 1988, Delilah served as curator for the exhibition “Inspiration: 1961-1989” which was held at the Smithsonian Anacostia Museum and featured the work of thirty-four African-American artists who were members of the District of Columbia Art Education Association. The exhibition, a survey of the works of its members demonstrated the extraordinary talent and served as stated by Ms. Pierce, “ in documenting the history and the staying power of an organization with more than twenty-five years of community involvement and a rich legacy of service.

She was a member of the Smith-Mason Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. and the Old Sculpin Gallery and Cousen Rose Gallery in Massachusetts.

Her work is in the permanent collections of the Smithsonian Museum of American Art, University of the District of Columbia, Howard University, Evans-Tibbs Collection, Barnett-Aden Collection, Smith-Mason Gallery of Art, Bowie State College.

Pierce attended Miner Normal (Miner Teachers College) and then Howard University where she earned a B.S. degree. She went on to receive a Masters in art and art education from Teachers College-Columbia University in New York City; and received an honorary degree, Doctor of Humane Letters, from the University of the District of Columbia, Washington, D.C. Pierce received an Agnes-Meyer Fellowship to study abroad in Europe, the Middle East and Africa. Her educational study includes travel to London, Paris, Holland, Rome, Greece, Lebanon, the Holy Land, the River Jordan, Cairo, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Ghana and Dakar.

I have been painting and drawing for most of my life and, in recent years making prints. These creative efforts are a means of grappling with the impulses and struggles that make up the way I see my place in the world. In a work of art I am pleased with, I have succeeded in wresting a sense of order from the chaos of an incomplete and unbalanced piece. I create the chaos and then I resolve it.

I have been painting and drawing for most of my life and, in recent years making prints. These creative efforts are a means of grappling with the impulses and struggles that make up the way I see my place in the world. In a work of art I am pleased with, I have succeeded in wresting a sense of order from the chaos of an incomplete and unbalanced piece. I create the chaos and then I resolve it.