Artist

Artist

Black Man in a Black World Artists Talk

Black Man in a Black World

September 2 – November 18, 2017

artwork | artists’ talk | the artist’s | film | music | press

Artist

Artist

September 2 – November 18, 2017

artwork | artists’ talk | the artist’s | film | music | press

Artist

Artist

Face Off II (detail), Archival Ink Jet Print, 30″ x 40″, 2014 by Larry Cook

September 2 – November 18, 2017

artwork | artists’ talk | the artist’s | film | music | press

I chose to use the human heart painted Black as a means of representing the Black body. The heart being the core of the body, the drum whose rhythm keeps us moving while Black Americans are the cultural, spiritual, and biological vanguard. The God Seed depicts the biological, giving us a black heart as the nucleus with golden barbed wire as electrons. This speaks to the origins of civilization as we know it; with all roots leading to Africa. While science has proven every human carries DNA strands of the Black woman, we know it takes two to populate – making the Black woman and man the Mother and Father of civilizations. (It would almost seem the Black man is intentionally left out of the equation).

Dark Matter takes us to the astrological tying in cultural and spiritual ties. In science dark Matter is both theoretical, and invisible as it does not reflect light, yet helps to explain things like gravitational forces. These invisible forces I place correlation to that of “soul” – the style and movements of Black men in particular. From the music we’ve created, to how we style our clothing, to the way we strut down a sidewalk, our soul is magnetic. It is an attracting force people worldwide gravitate toward with hopes to bask in the feeling and replicate for themselves. This desire to be entangled in our soulfulness I interpret almost as a form of worship. Dark Matter is presented to the viewer as a salvaged relic-like object—broken and missing pieces yet preserved and placed on display for all to see. The rusted and broken hinges give the sense that this three-part panel was once connected, possibly unfolding from the center, offering a visual presence reminiscent of alters in catholic churches.

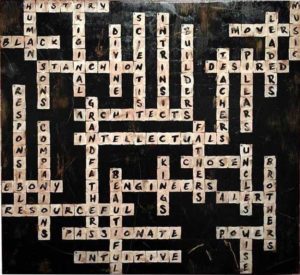

Factualism is simply a meditation on whom and what Black men truly are. It is meant as the antithesis of what pop culture and the news m/entertainment media present us as. It’s an exercise in defining oneself and taking hold of one’s own agency. It’s the presentation of another set of facts not often put on display. The words and ideas are given to the viewer in the form of a crossword puzzle to help think about how these ideas intersect and build off one another, giving viewers a new set of images to aid contextualizing their thoughts on Black men.

Do For Self and The Call pay homage to black liberation philosophies that arose out of organizations such as the Nation of Islam and the Moorish Science Temple. Each work references a sector of Black trade and industry that is a part of our cultural memory. In Do For Self, oil based colognes signify vendor customs established within the black community. In The Call, a reproduction of the Nation of Islam’s weekly The Final Call observes that recordings of personal histories within black community can equate to economic independence, self-worth, and empowerment.

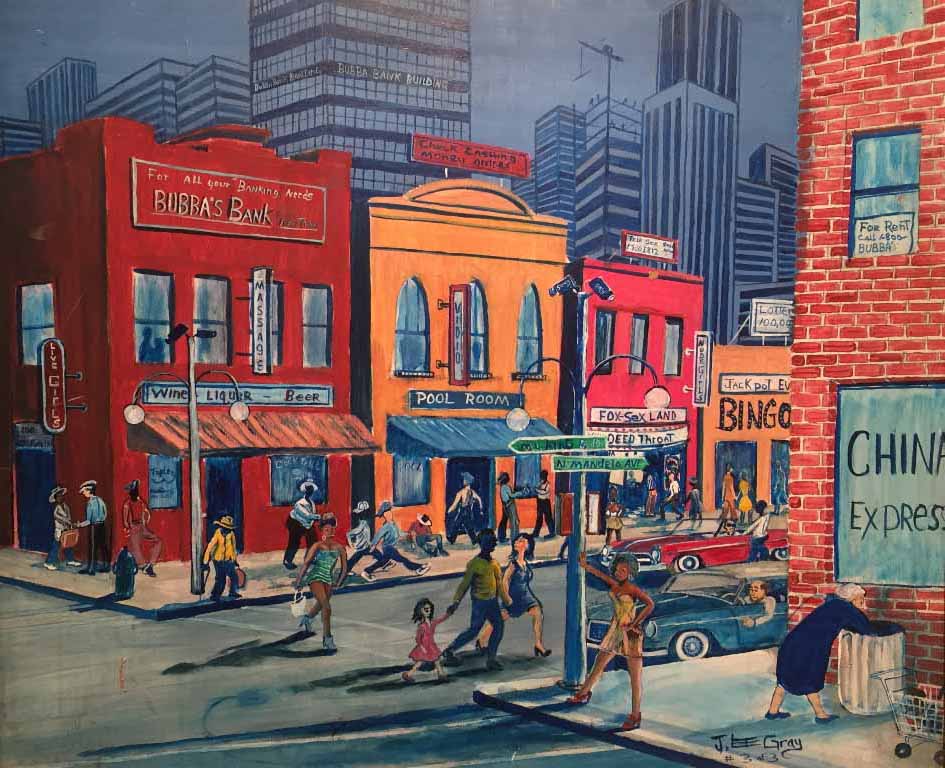

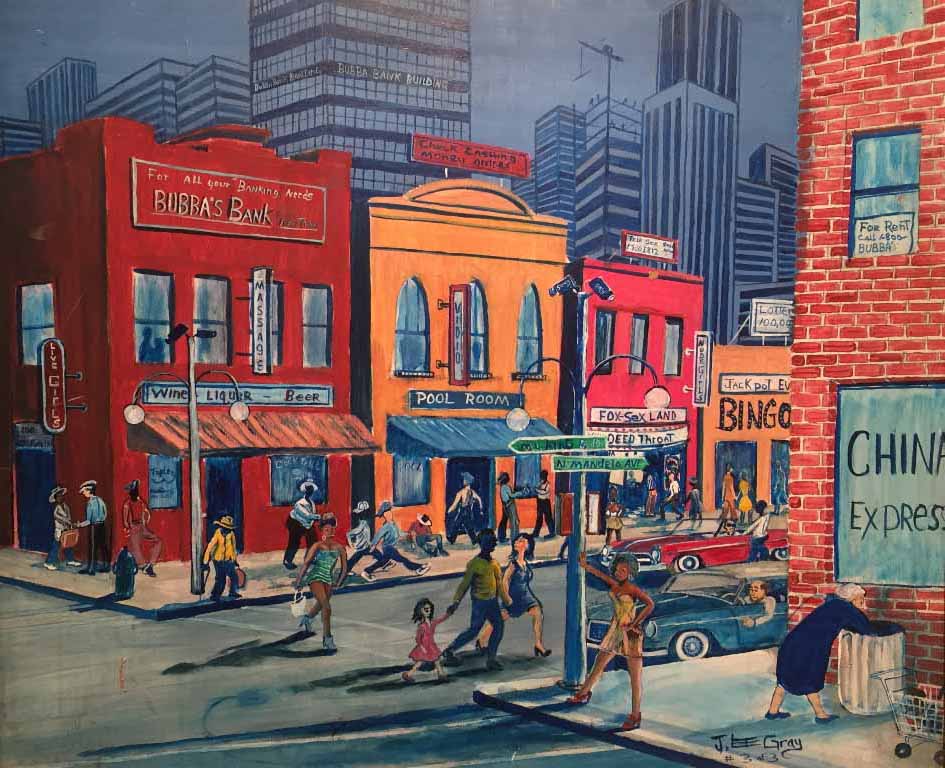

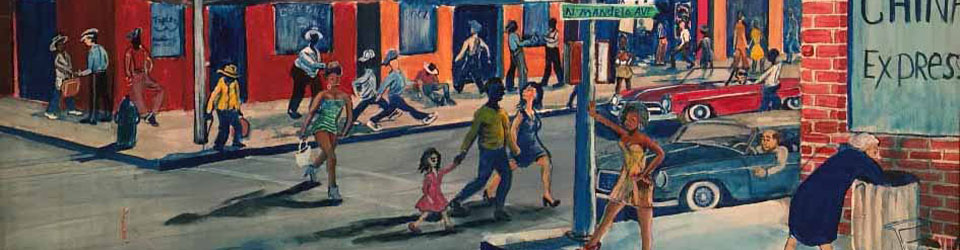

“Johnnie Lee Gray’s Paintings in the Context of Jim Crow” Book title: Rising Above Jim Crow: The Paintings of Johnnie Lee Gray. Published by New York Life. Excerpt from essay written by Gwen Everett, PH.D.

The exhibition Black Man in a Black World couldn’t be more timely, when demonstrations of bigotry and hate are assigned the moral equivalency of people fighting for human dignity, equality and justice for all members of the human family. African Americans and all marginalized people need to be heard, recorded and acknowledged for what they have endured, for their significance, and for their strength. Through my paintings I consider historical and contemporary truths attempting to reveal the dignity, endurance, and genius of African Americans hoping to evoke dialogue and reflection on implicit bias and resulting perpetrated injustices committed towards people of color in this country.

In this body of work, it is my intent to “flip” the role of the Black Man from the degradation of subservience to the triumphant role of hero using images traditionally assigned to white males.

The Fighter exemplifies the Black Man’s clash against oppression, degradation and exploitation. The daily assaults and dog whistle status reminders requires nothing less than emotional resistance, determination and resilience.

Minstrel’s Guide this black harlequin harks back to the 1500s as he moves into the viewer’s space to then morph into the minstrel of the 1800-1900s. Minstrels were derogatory characterizations, created by the dominant culture as entertainment to ridicule blacks after the Civil War.

Sampson Brings Down the House recalls the biblical image of a white curly locked Sampson tearing down the temple. Here it is flipped, showing a Black Sampson tearing down the house of injustice. It is my intent to show the strength and prowess of the Black Man in overcoming enormous odds.

Push Back depicts the strong Black male pushing back against racism, bigotry, hatred, inequities, prejudice, discrimination, white supremacy, etc., etc…..

Strange Tale is based on the mythology of Europa and Jupiter, here used to represent the “peculiar institution” of slavery and its aftermath.

The work Sampson and the Lion is based on the biblical story of Sampson slaying the lion that roared against him, flipped here to show a strong Black Sampson combating oppression.

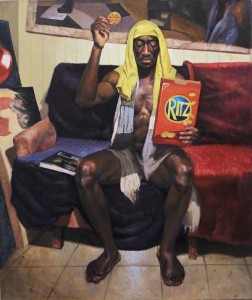

Growing up we feared for our lives. Dropping the wafers or chewing too fast would result in going to hell, so we would impersonate Jesus distributing the holy wafers, to practice receiving the Eucharist correctly. Ritz crackers were usually the practice food of choice to simulate the daunting experience, not to mention they were addictive. Since Jesus was white, according to Catholic imagery, a shirt was always used as a wig to help sell the idea of flowing hair.

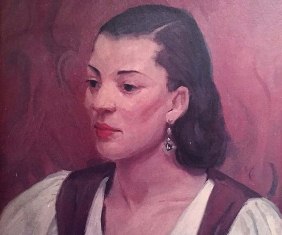

Chosen by Myrtis Bedolla, Founding Director, Galerie Myrtis are selected works of cultural and historical significance offered from private collections. Featured Artists: Antonio Blackburn, Augustus Dunbier, Adolphus Ealey, Johnnie Lee Gray, Thomas Moran, Stephanie Pogue and Lucille Malkia Roberts.

Augustus William Dunbier, Negro Woman, 1934, Oil on Canvas Board, 33 1/2″H x 27 1/2″W (framed), Provenance: Jacqueline Miller Collection gift from Adolphus Ealey, The Barnett Aden Collection

Artist

Artist

Johnnie Lee Gray was born in Spartanburg County, South Carolina in 1941. In his early years Gray demonstrated artistic talent, painting and drawing as a way to express his emotions and depict his surroundings. Working alongside his grandparents in the fields of their sharecropper farm, and later as a carpenter, textile mill worker, house painter, Gray learned early on to use the materials of his milieu to create works of art that drew on his memories and experiences as a black American man. read full biography

Artist

Artist

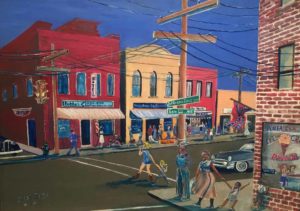

After graduating from the county’s segregated Lincoln High School in 1960, Gray enlisted in the Army, where he served for seven years, including an 18-month volunteer tour of duty in Vietnam. As a Vietnam Veteran and self-taught artist, Gray’s work illustrated his experiences in the military as an African-American and the participation of black people in the history of the American and world landscape. Described as “visionary” “outsider” artist, the patterned shapes, visual texture, vibrant palettes and repetitive forms showcased in his paintings are recognizable characteristics of his historical narratives. read full bio

Artist

Artist

After graduating from the county’s segregated Lincoln High School in 1960, Gray enlisted in the Army, where he served for seven years, including an 18-month volunteer tour of duty in Vietnam. As a Vietnam Veteran and self-taught artist, Gray’s work illustrated his experiences in the military as an African-American and the participation of black people in the history of the American and world landscape. Described as “visionary” “outsider” artist, the patterned shapes, visual texture, vibrant palettes and repetitive forms showcased in his paintings are recognizable characteristics of his historical narratives.

Recently earning his spot in history along notable artists like Jacob Lawrence and Robert Colescott, Gray’s parting prayer was that his wife of 22 years, Shirley Sims Gray, would be blessed through his artwork and provided for after he passed (2000). Mrs. Gray later went on to establish Art by J. Lee Gray, Inc, and serves as the CEO for this private collection. In 2004, one of his paintings—depicting sharecroppers picking cotton—sold for $100,000, a significant price for the work of an outsider artist.

A pivotal point in Johnnie Lee Gray’s career came after his death, when PBS and Thirteen/WNET New York reached out to Mrs.Gray to conduct an interview for their ongoing research on the African-American experience with legally enforced segregation, otherwise known as Jim Crow. While interviewing her, researchers discovered her husband’s extensive body of work revealing the storyteller they were looking for. Shortly after New York Life Insurance Company became the official corporate sponsor for the television series The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow, airing nationally in the fall of 2002, which prominently featured Grays work. This new attention and recognition prompted a traveling exhibition in 2003, curated by Dr. Gwendolyn H. Everett of Howard University, with its official opening night at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in Harlem, NY.

From 2003-2009, Johnnie Lee Gray’s work was exhibited in such venues as the Russell Senate Office Building Rotunda, Washington D.C.; The Forbes Galleries, Manhattan, NY; Chicago Historical Society, Chicago, IL; Atlanta History Center, Atlanta, GA; California State University, Northridge, CA; the Spartanburg County Museum of Art, SC; University of Virginia Art Museum, Charlottesville, VA; Gibbes Museum of Art, Charleston, SC; Morris Museum of Art, Augusta, GA; Livingstone College, Salisbury, NC; Converse College Milliken Art Gallery, Spartanburg, SC; the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Harlem, NY; and the Cherokee County History & Arts Museum, Gaffney, SC. 1

Significant exhibitions include traveling solo exhibits: “Rising Above Jim Crow: The paintings of Johnnie Lee Gray”, 2003 and “Landscape of Slavery: The Plantation in American Art”, 2007-2008.

1 Biography information sourced from Rising Above Jim Crow: The Paintings of Johnnie Lee Gray by Dr. Gwendolyn H. Everett, PH.D., 2004, New York Life Insurance Company

Exhibitions

Exhibitions

Johnnie Lee Gray, The Revolution: Separate But Equal (detail) – Jim Crow Series, Acrylic on plywood, 20 5/8″H x 27 5/8″W

Chosen by Myrtis Bedolla, Founding Director, Galerie Myrtis are selected works of cultural and historical significance offered from private collections. Featured Artists: Antonio Blackburn, Augustus Dunbier, Adolphus Ealey, Johnnie Lee Gray, Thomas Moran, Stephanie Pogue and Lucille Malkia Roberts.

Secondary Market

Secondary Market

The Secondary Art Market includes works of art that have been sold before and are available again for sale in the market place. Galerie Myrtis offers personalized divestment strategies to art collectors seeking to sell works through art auctions or private resale. Our expertise in the local, national and international art markets allows us to negotiate profitable sales for clients. We also offer confidential auction representation. For more information call 410-235-3711 or at sales@galeriemyrtis.com

Galerie Myrtis Extra! 15 Tips for Building a Fine Art Collection